Shepard Fairey: ‘My goal was to make art by any means necessary’

The street artist, famous for his Obama image, could get a 10-year jail sentence for vandalism in Detroit, but meanwhile has a New York gallery exhibition

Adrian Brune

Friday 16 October 2015 13.42 EDT

When the artist Diego Rivera arrived in Detroit in April 1932 – at the behest of auto magnate Edsel Ford – to create the Detroit Industry murals, he entered an industrial colossus laid low by the great depression and amplified by a chorus of conservative critics, who called his mixed-race, humanistic portrayal of the working class, “coarse in conception … foolishly vulgar, and a slander to Detroit workmen”.

More than 80 years later, street artist Shepard Fairey turned up in Detroit – at the invitation of billionaire fringe banking mogul Dan Gilbert – to paint several murals in the demolished and demoralised city. He also allegedly put up some illegal posters, which city officials described as vandalism. Now he faces 10 years in prison and fines exceeding $10,000.

Rivera was eventually renowned as the greatest Mexican artist of the 20th century. Fairey, whose most recent show, On Our Hands, is currently showing at Jacob Lewis in New York, awaits his verdict both in Detroit and the arena of public opinion. In the city, the One Campus Martius building is now home to his 18-storey mural, while the historical Wurlitzer and Vanity Ballroom buildings still have his illegally plastered posters, which feature his Obey Giant tag, adhered to their walls.

“To some people street art is vandalism, to others it’s gentrification, and either of those could be considered more legit than the other depending on your perspective,” says Fairey, an admirer of Rivera, by email. Although not permitted to talk about his current legal troubles in Detroit, for which he will stand trial on 26 January 2016, Fairey said that when outsider art was accepted, it often wound up in “the narrow bits of important historical documentation”.

“A lot of great things fall through the cracks in terms of art history or general history,” he added. “Other than that caveat, I really don’t care about the concept of legitimacy from anyone else’s perspective other than mine.”

On Our Hands, the first solo exhibition of Fairey’s paintings in New York City since 2010, coincides with Covert to Overt, a 256-page coffee-table book showcasing everything from his most recent works on paper to large-scale installations and his return to public artworks.

However, neither the book nor the show mean that Fairey has left his roots. “I went to art school and I’ve drawn and painted my whole life – my goal was to make art by any means necessary,” he says. “For a long time that meant street art and T-shirts were my only options. Now I have a lot more options.”

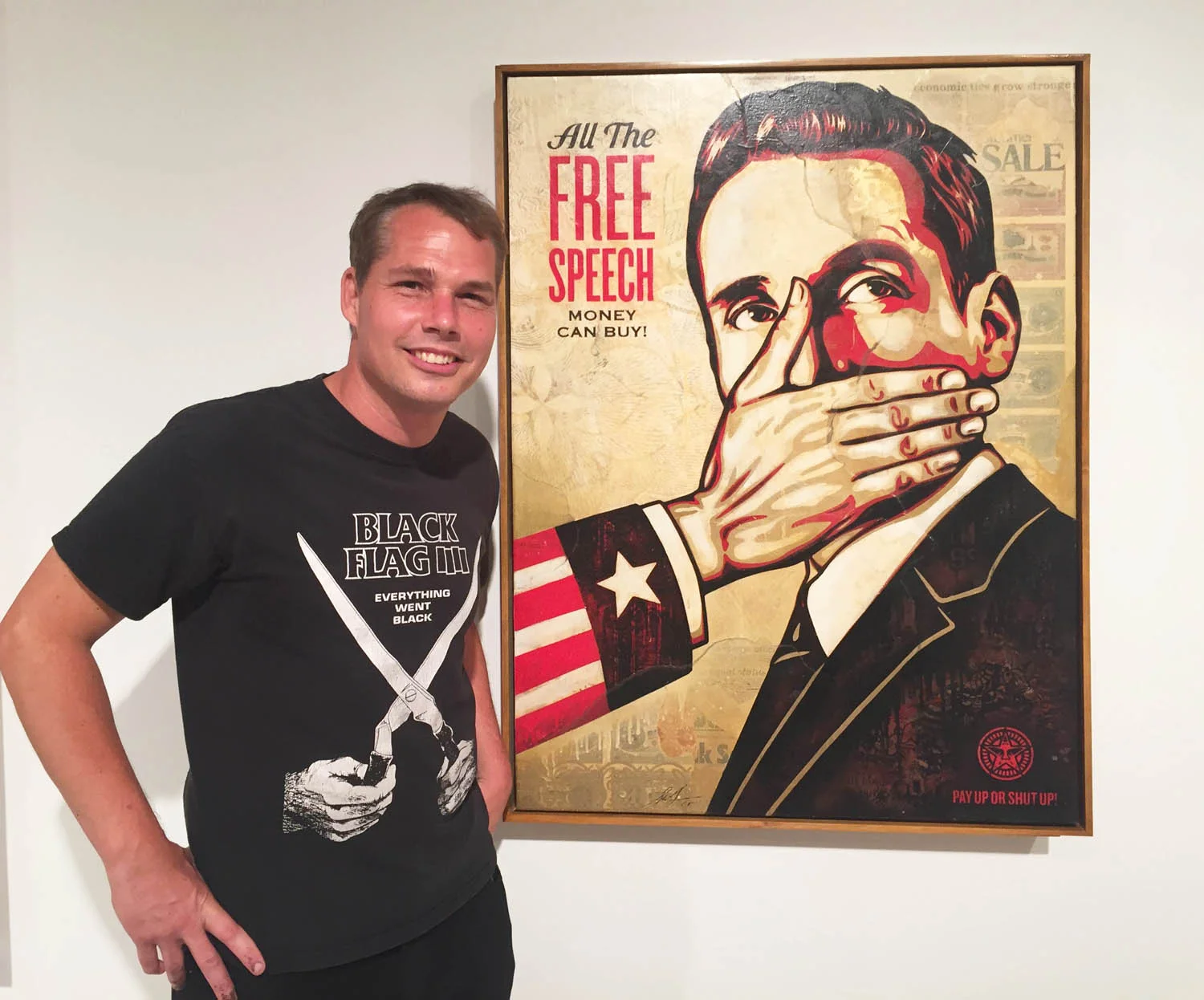

Rather than just gaining attention, however, for bigger and badder Obey branding, Fairey’s show has been cited by the New York Times as “considerably more complex” than his previous work. With mixed-media painting built up from layers of rich designs – the base of which consists of Fairey’s detailed stencilling of faux newspaper print – Fairey evokes communist propaganda, Barbara Kruger-style advertorials and Jasper Johns subversion. He has also ventured into sculpture, with one particularly poignant bronze, emulating a late-1950s trophy featuring a soldier in full weaponry standing atop a decorative grenade.

“I share my art through a lot of platforms, and making art pieces that I can put a lot of time into is one of the important ways I can communicate with an audience,” Fairey says. “I felt it was time to show a new body of fine art as a collection rather than disparate images.”

On Our Hands also demonstrates the disillusion Fairey – best known for his “Hope” poster co-opted by the 2008 Obama presidential campaign – has experienced in an era of promise beginning with the United States’ election of its first black president. Citing his dismay over Obama’s use of drones in Pakistan and the Middle East, as well as the administration’s continuation of the domestic surveillance programs, Fairey said he has “come to realise that the problems are not dependent on the actions of one person” but are largely symptoms of a broken system where corporations and oligarchs corrupt democracy.

Shepard Fairey’s On Our Hands. Photograph: Jacob Lewis Gallery

“Americans need to stop being obsessed with personalities and start looking more closely at the principles that are at play within the dynamics of our system. The players change but the problems stay the same.”

Rivera, said in reflection of his life and controversies, including Detroit, that an artist is “above all a human being, profoundly human to the core”. If the artist “won’t put down his magic brush and head the fight against the oppressor, then he isn’t a great artist”.

Fairey, too, remains steadfast in the principles and perspectives he acquired following his years at the prestigious Rhode Island School of Design and his ascendancy through the ranks of street art: to enable people to clearly see objects or ideas so taken for granted that they have become invisible.

“Ten years ago I thought that hard work and moving up through the various stages of societal and cultural validation would make me feel secure and satisfied,” he says. “Now, I would tell anyone that the most important thing is to be honest with yourself and be happy if you feel you’ve accomplished your vision – no matter what the rest of the world has to say.”

On Our Hands runs through 24 October at the Jacob Lewis Gallery, 521 West 26th Street, New York