AN OKLAHOMA SON AIRS HIS FAMILY SECRETS

by Adrian Margaret Brune

01/28/2016

By the early 1970s, the writer John Cheever had slipped beyond alcoholic; his prodigious drinking had likely caused permanent nerve damage. So he decided to give Alcoholics Anonymous a try.

No one can know if Cheever, the chronicler of the disaffected suburban class, was prepared to divulge all of his timeworn secrets—his abusive behavior, his bisexuality, and his self-loathing—at his AA meetings. Cheever had always bowed down before the alter of literature: “Literature has been the salvation of the damned… routed despair and can perhaps in this case save the world,” he wrote in his journal before his last public appearance, the ceremony at which he received the National Medal for Literature in 1982.

Blake Bailey, an Oklahoma-born biographer who wrote the authoritative book on John Cheever, as well novelists Richard Yates and Charles Jackson, never seriously considered authoring his own memoir until he was confronted “with a tragedy so mystifying” he had to find a way “to capture the quiddity.”

The Splendid Things We Planned, his memoir about his older brother, Scott, and his adolescence in an affluent, antipathetical Oklahoma City family is the product of that personal examination. The acclaimed book, a finalist for the 2015 National Book Critics Circle Award, took 11 years and several drafts until print, but with the candor and purpose of a diviner, Bailey pulls back the curtain on the effects of affluence, restlessness, ladder-climbing, personality clashes, and perhaps mental illness on Scott and all the people surrounding him.

“Scott didn’t exist in a vacuum; my family had something to do with it,” Bailey said last March in New York before the Critics Circle awards dinner. “My family was very, very strange—we were four people who wanted to be in four different places at the same time.”

Bailey introduces the book with an anecdote about Scott’s first months as a newborn in New York, where his father, Burck Bailey, a Root-Tilden scholar at New York University’s School of Law, struggled to care for his German-born wife, Marlies, and his son, who would “emit one heart-shriveling shriek after another… as if screaming helped him concentrate on some larger plan.” With no other way to mollify the baby, Bailey’s parents joked to friends that they carried Scott to the roof of their tiny McDougal Street apartment and contemplated “whether to throw him or themselves off,” Bailey wrote in Splendid Things. Instead, Burck took his German wife and toddler to Oklahoma.

In Oklahoma City, four hours away from his birthplace of Vinita, Burck Bailey found career success as one of the youngest assistant attorney general in the state’s history, then he rose through the annals of Oklahoma law as a partner at Fellers, Snider, Blankenship, Bailey & Tippens, P.C. Despite a reputation as a top trial attorney and three trips to the U.S. Supreme Court, Burck cut a passive, if not mollifying figure at home, succumbing to nearly every whim of Marlies. He moved his family—which, by 1972, included nine-year-old Blake Bailey—to the outskirts of the city so she could raise Arabian horses. He supported Marlies’ enrollment in the University of Oklahoma (where she would eventually earn a Master’s in Anthropology). And he funded her social life, including lavish parties with students from cultural exchange programs and friends from school.

With both an absent father and a mother who felt robbed of her youth and wanted to be anywhere but home, Scott Bailey lived without boundaries, to the envy and the vexing of his younger brother, whom, with his fluent German, Scott called Zwiebel Mund—“onion mouth”—or just Zwieb, for the sake of brevity.

“And what, in turn, did I call Scott? I called him a very matter-of-fact (or deploring)Scott. No endearments on my end,” Bailey wrote. The name game provided a harbinger of their relationship for the next 40 years—the vain, yet needy, older brother living beyond his means (the family Porsche and its ruin at the hands of Scott as the key metaphor), descending deeper into drugs and chaos, getting rescued and repeating the process. The younger brother used him as an example of how not to live and although he falters at times, especially after a wild life at Tulane University in decadent New Orleans, ultimately succeeds at a happy existence.

“We were two brothers, whose lives went in completely different directions,” said Bailey, now a professor of Creative Writing at Old Dominion University in Norfolk, Virginia. “I looked at him and I was able to correct my mistakes. In that sense, I owe my successes to the depreciation of Scott’s life.

“I don’t think Scott wanted to accept that his inability to mesh with society was his problem. He knew ultimately his situation was hopeless and that he was fucked up, yet he was the foremost apologist for it.”

Growing up in a privileged Oklahoma family in which siblings thrive or crash-and-burn is not a new phenomenon—the difference is Bailey’s willingness to publish his story. “My own philosophy can be summed up in two quotes. Voltaire: ‘We owe nothing to the dead but the truth’; and Capote’s biographer Gerald Clark—and I’m paraphrasing—‘I just assumed I could say whatever I wanted, and that’s what I did.’

“I think there are genuinely malicious biographers who are out to get the dirty laundry, and that’s what’s almost exclusively featured in their books. But I view biography as an empirical endeavor foremost: you gather as much evidence as you can find, then you give each theme just as much emphasis as it deserves relative to the life.”

The book is sometimes just as much about Bailey as it is about his brother.

Blake, who floundered in New York and on Capitol Hill in Washington, D.C., eventually returned to New Orleans and started teaching gifted children. “I was writing bad fiction—and had just finished my third unpublished novel—when an agent friend of mine said, ‘Blake, this is not good. Why don’t you put together a proposal on something nonfiction.’

“At the time, I really just wanted to find out about Richard Yates—I never thought of myself as a biographer.” However, after coming in as a finalist for the 2003 National Book Critics Circle Award for A Tragic Honesty: The Life and Times of Richard Yates, he took on author John Cheever. In 2009, he produced Cheever: A Life, which also won the National Book Critics Circle Award, the Parkman Prize, and a nod from the Pulitzer board.

Just after finishing Farther & Wilder: The Lost Weekends and Literary Dreams of Charles Jackson, Bailey finished Splendid Things. Bailey’s detachment in Splendid Things, however, is palpable—it’s an autobiography written with a biographer’s eye.

By his account, Bailey’s surviving family was not initially pleased with Splendid Things, despite its eventual success. However, Burck, who had moved to Santa Fe with his second wife and had not seen his second son for 10 years, eventually reunited with him. “I think he was pleasantly surprised how sympathetic it was to him and got back in touch,” according to Bailey.

Marlies, to whom Splendid Things is dedicated (in addition to Scott Bailey), denied the things Bailey had written about his childhood, but when he gave the opportunity to make corrections, “she wrote far more damning versions than anything I had put down,” he said. “Now she presses the book on anyone she meets.”

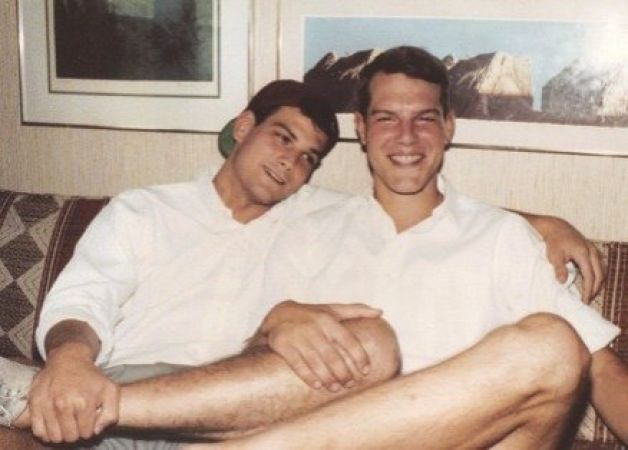

Cheever scholars hardly debate that two of Cheever’s best works of fiction—the novelFalconer and the New Yorker story “Goodbye, My Brother”—narrate extreme brotherly contests that result in violence and fratricide. And as John Cheever once told a psychiatrist, his older brother, Frederick, was the most “significant relationship in his life.” Whether intentionally or not, so it seems with Blake Bailey. A photo of the two as teenagers, Blake Bailey looking with admiration upon his older brother, adorns the back cover jacket. “In as far as he loved anyone, I know that Scott loved me,” Bailey said.