Attacks and threats of violence are forcing schools in the region to close. Meet the children who are determined to keep learning.

Hussaini*, 14, is one of the lucky ones. He escaped. In 2018, as terrorism by extremist groups in the Sahel crossed into Burkina Faso, his village was attacked while he was in school. First, he heard screaming, and then gunfire. “They shot at our teachers and killed one of them,” he says. “They burned dwn the classrooms.” Hussaini ran home and within a matter of minutes, his family set off. They left everything behind, including school. Since that day, Hussaini has not set foot in a classroom. “I used to love school, to read, to count and to play during recess,” he says. “It’s been a year since I last went...”

While attacks on military outposts are relatively common in West and Central Africa, until recently, schools were not often affected. But from the end of June 2017 to June 2019, the number of schools forced to close due to rising insecurity tripled. More than 9,200 schools closed across Burkina Faso, Cameroon, the Central African Republic, Chad, the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Mali, Niger and Nigeria, leaving 1.91 million children without education. These children face a much higher risk of recruitment by armed groups, gender-based violence and targeting by traffickers.

But in desperate times, innovation offers solutions. Thanks to a radio set he received as part of the UNICEF-backed Radio Education in Emergencies programme, Hussaini is still learning every day. Along with radio lessons in literacy and numeracy, Hussaini works with a trained facilitator, Abdoulaye*, 23, who visits him regularly to help with his comprehension. “It’s good. All the family listens to the [radio] lessons now,” says Hussaini. But he still misses his old school. “We had good teachers,” he recalls. “I don’t know where they are today.”

A row of old desks lies across the road on the outskirts of Banki, Nigeria on 1 May 2019. Although the town is still considered one of the most dangerous places in Borno State and is largely deserted, its local primary school has reopened. Refurbished with support from UNICEF, it now has a high perimeter wall, entry and exit gates, and teachers who have been trained to provide psychosocial support.

Maïmouna Barry, 45, walks through what is left of the village of Ogossagou-Peulh, Mali, on 2 April 2019 with her daughter Hawa, 10. Less than two weeks before, Maïmouna lost her youngest daughter during an attack on the village, which left more than 150 people dead, one-third of whom were children. With the help of UNICEF, community learning centres are being set up across the central Sahel region, as safe spaces for children to study, play and receive psychosocial support.

Four years ago, violent militias attacked Banki, Nigeria, the village where Bintu Mohammed, 13, lives. “I was in school in the morning and then I went home and… we ran, everyone ran,” she says. “They burned the school down. I was so upset, I felt like my dreams would never be achieved.” After returning from two years in Cameroon, Bintu enrolled in a rebuilt school. “I’m so happy to be back… I will be educated,” Bintu says standing in her home on 1 May 2019.

Delphine Bikajuri, Principal of GEPS Youpwe, a UNICEF-supported government primary school, goes over lesson plans in Douala, Cameroon on 21 May 2019. Two years ago, Ms. Bikajuri had to arrange the release of her own daughter after armed groups kidnapped her from a high school in North-West Cameroon, one of two English-speaking provinces. The soldiers called Ms. Bikajuri and her husband traitors because they teach. "How would children be leaders of tomorrow, if they are not educated?" she asks.

Children take part in an emergency attack simulation and practice sheltering in the event of an assault, at the Yalgho Primary School in Dori, Burkina Faso on 26 June 2019. Threats to teachers, ambushes on schools and the use of schools for military purposes have forced 4,505 schools in the country to close, disrupting education for more than 626,693 children.

A student goes over blackboard notes on emergency preparedness at a school in Baigaï, a village in Cameroon near the border with Nigeria on 26 May 2019. The programme focusses on teaching children and teachers how to mitigate an armed attack. Despite the risks, people on the front lines of this struggle will not rest until children in their communities are guaranteed the education that is every child’s right.

Ideological opposition to what is seen as Western-style education, especially for girls, is central to many of the disputes that ravage the region. As a result, schoolchildren, teachers and administrators are being deliberately targeted. Children participate in an armed assault simulation during an emergency drill in Baigaï on 26 May 2019.

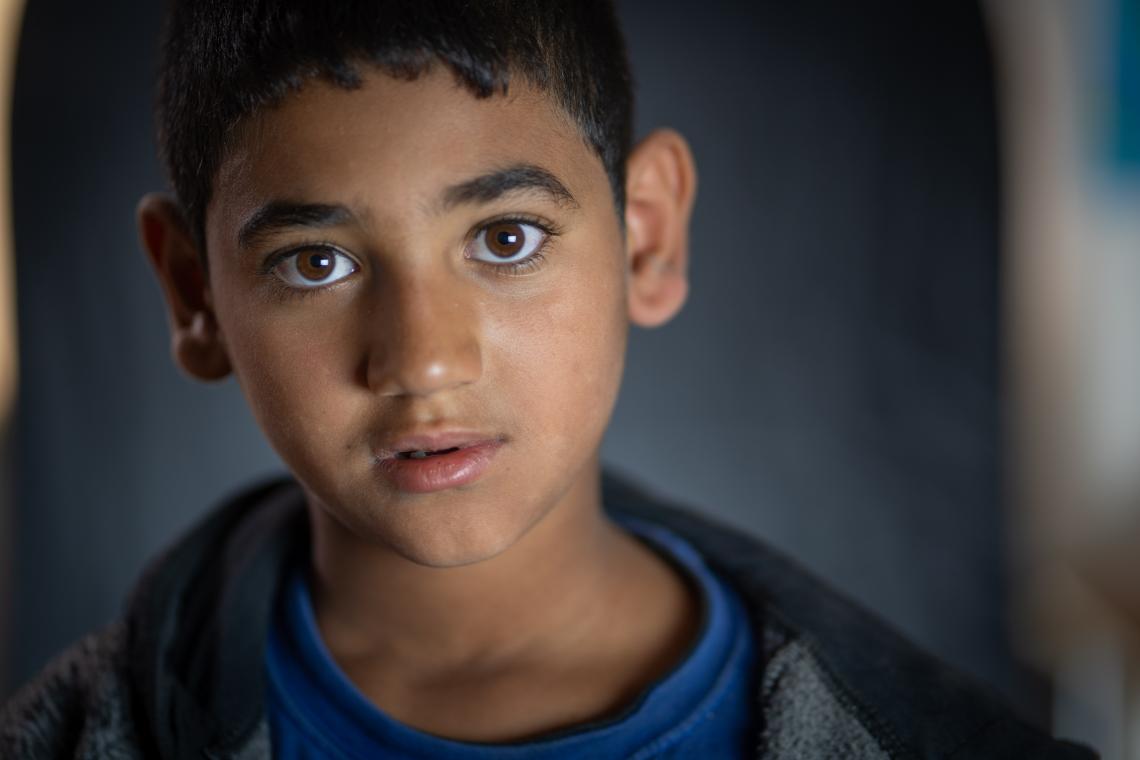

“My father said we have to leave, and so we did, all of us: my parents, grandparents, my sisters and brothers. We all escaped together.” Hussaini has not set foot in a classroom since that day his village was attacked, he explains while drawing pictures during a lesson through the Radio Education in Emergencies programme in Dori, Burkina Faso on 25 June 2019. But his Radio Education facilitator has become a trusted friend. “Abdoulaye is like my older brother,” Hussaini says.

Abdoulaye (left) guides Hussaini through his lesson on 25 June 2019. Abdoulaye says that people have been deeply affected by the crisis. “At first, they only threatened schools,” he says. “Nowadays, they actually kill us.” But he insists that he has not been deterred. “It’s very important for these children to learn,” he says. “They are our younger brothers and sisters. We must help them.”

"Back home, I liked going to school," says Bouba, a survivor of a militant strike on his home village, while herding cows in Baigaï on 25 May 2019. "I was good at maths, and I even liked doing homework.” In his spare time, Bouba attends the UNICEF-sponsored 'radio school', which takes place under the shade of large tree in the government school courtyard. “Now, when I see other children returning from school during the day, I want to be among them,” he adds.