JANUARY 29, 2016

In the final months of 2012, investigators in Kenya found the battered and lifeless body of Peninah Nyambura, stuffed in a drainage ditch in Thika, a small industrial town 25 miles outside of Nairobi. Nyambura was the mother of a 13-year-old daughter. She was also a Kenyan sex worker, and hers was the fourth murder of a sex worker in Thika in two years.

The day of Nyambura’s funeral, more than 300 Kenyan sex workers converged on Thika to demand a police investigation and lead a peaceful protest, with Nyambura’s body lying in a hearse that followed. When the crowd reached the police commissioner’s gate, Nyambura’s daughter spoke out: “The murderer killed the person who put food on my table. He killed the only source of money for me to go to school. He killed the only person who supported me...” Police officers brandished their guns and threatened the sex workers with tear gas, but they continued to march.

Anti-prostitution scholars and activists have long argued that any exchange of sexual services for payment is an inherently violent and coercive act that degrades women. Professor Chi Adanna Mgbako does not tend to buy this monolithic argument. She contends that, in a world where a vast majority of workers have limited opportunities, individuals do make the rational decision to pursue sex work, and the abuses they experience don’t occur because the selling of sexual services is necessarily degrading or dehumanizing. The abuses are, instead, structural, including laws that criminalize sex work and the discrimination of the police.

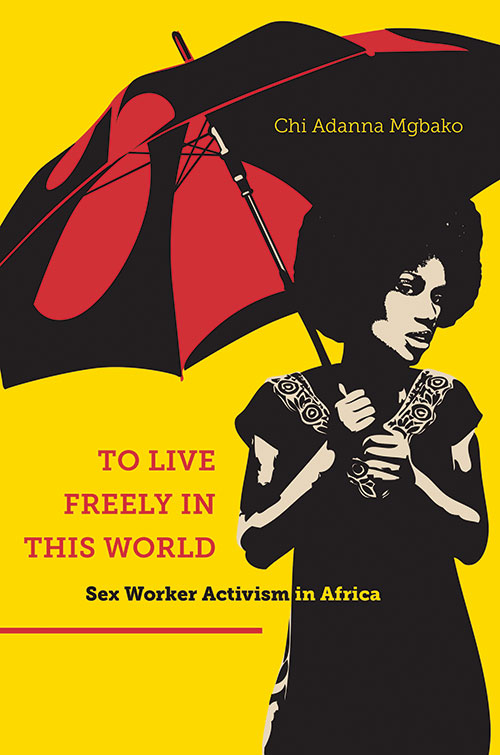

Yet in the midst of the chronic violence and stigma, African sex workers have sparked a sex workers’ rights movement that continues to spread across the continent. For the past nine years, Mgbako has worked with the sex workers’ rights movement and its human rights components—experience that informs her new book, To Live Freely in This World: Sex Worker Activism in Africa, released earlier this month.

The book was officially launched on January 26 at Fordham Law with a panel moderated by Professor Clare Huntington, associate dean for research, and which included Kholi Buthelezi, the director of Sisonke, a sex worker advocacy organization in South Africa.

“I interviewed almost 200 sex workers, most of whom had been hairdressers, domestic workers, and factory employees,” Mgbako said. “They would tell me ‘I was making this much in my old job, but my friend was making 20 percent more doing sex work, so I started doing sex work. They didn’t see their work in black-and-white terms. Some aspects were empowering; some were exploitative.

“They were asking the question, ‘How do I have more power and control over my labor? How do I do this safely?’ It was really simple; it was about the accumulation of capital.”

Mgbako has long been interested in human rights, and she remembers particularly well during her law school days at Harvard a seminar course on international women’s rights, which covered female genital cutting, women’s increased political participation in her country, and reproductive freedom.

“The class on prostitution was different. Gone were the voices directly from affected communities that had so illuminated other parts of the course,” she wrote in To Live Freely. “Instead, we read a slew of articles by the New York Times columnist Nicholas Kristof on what struck me as his misguided efforts to liberate ‘sex slaves’ from brothels in Southeast Asia by purchasing them. We read nothing from sex workers themselves.”

Coming away from that seminal class with a fierce belief in the notion of community and individual agency, Mgbako determined to find the sex workers’ voices. One of her first allies was Buthelezi, who helped launch Sisonke in 2003 after a group of 76 sex workers from across South Africa decided to take responsibility for effecting the changes in working conditions and equal rights that they sought.

“The biggest challenges we face come from a lack of justice and accountability by the police. Without that, everyone feels like they can take advantage of you,” said Buthelezi, who will accompany Mgbako on a two-week book tour. “I took a phone call on Saturday, before I left for the States. One of the workers was with a client, and he did not want to use a condom. When she asserted herself, he beat her up and took her money.

“She went to the [police]station and was called to come back but now is afraid to go back because she could be arrested or threatened. Everyone knows we have nowhere to go if we’re hurt or abused. We try to educate and empower around basic rights.”

Mgbako’s book focuses on African sex workers who are engaged in what is traditionally viewed as prostitution—the in-person physical exchange of sexual services for money or goods—but she does not limit the workers to straight, cisgender women. Rather, Mgbako argues that the lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender community in Africa, as well as its growing visibility, has pushed the movement forward.

“Intersectional movement-building between African sex worker and LGBT organizing is rooted in many factors but especially in an emotional solidarity that has formed between two communities that have been othered and oftentimes discarded by their societies—a camaraderie among those who have fought against the notion that their lives don’t matter, that they aren’t worthy of rights, respect, and dignity,” Mgbako wrote in the book.

Sex work existed in Africa before colonialism, not the other way around, as sometimes stated in history books, Mgbako said. Anti-gay laws and anti-sex work laws came with colonialism. “Uganda, where the criminal code comes from the British code, has some of the most stringent anti-gay and anti-sex work laws in Africa,” she added.

Countries such as South Africa and Kenya, which have rich histories of activism against oppression, apartheid, and colonialism, have proved the best launching pads for sex worker–led movements. The activism has also taken hold, but more slowly, in countries with weaker civil societies and without strong histories of social activism, like Mauritius and Botswana, while the highly publicized and serious legal and social crackdowns against those viewed as gender and sexual deviants have fueled the movements in Uganda and Nigeria.

Sex workers across the world are aiming not for legalization of prostitution but decriminalization. In New Zealand, sex work has been decriminalized through the Prostitution Reform Act, which grants any citizen over the age of 18 years the right to sell sexual services on the street or in a brothel and guarantees sex workers’ rights through employment laws.

While African sex workers still have a long fight ahead, the response from human rights groups and international bodies has been positive. In 2013, Human Rights Watch, the world’s leading international human rights organization, publicly affirmed that it had “concluded that ending the criminalization of sex work is critical to achieving public health and human rights goals.” In its 2014 World Report the organization reiterated its “push for decriminalizing voluntary sex work by adults.”

Mostly, however, Mgbako said that through the book, she and her students have learned about redefining their scope of human rights.

“Many of the sex worker activists profiled in this book have experienced horrendous abuse. But people who have experienced abuse are not bereft of agency,” Mgbako said. “A history of personal trauma may—or may not—directly inform people’s economic choices, but it should never be used as an excuse to negate their right and ability to speak about the truth of their own lives. There are no broken people in this book.”