Art Of Freedom

Exhibit Depicts The Joy, Violence Of Emancipation In Jamaica

October 05, 2007|By ADRIAN BRUNE; Special To The Courant

In 19th-century Jamaica when everyone heard the cry on Christmas Day, "Jonkonnu a come!'' it meant the pageantry and festival was about to begin in the town squares.

Artist Isaac Mendes Belisario followed, sketchbook in hand.

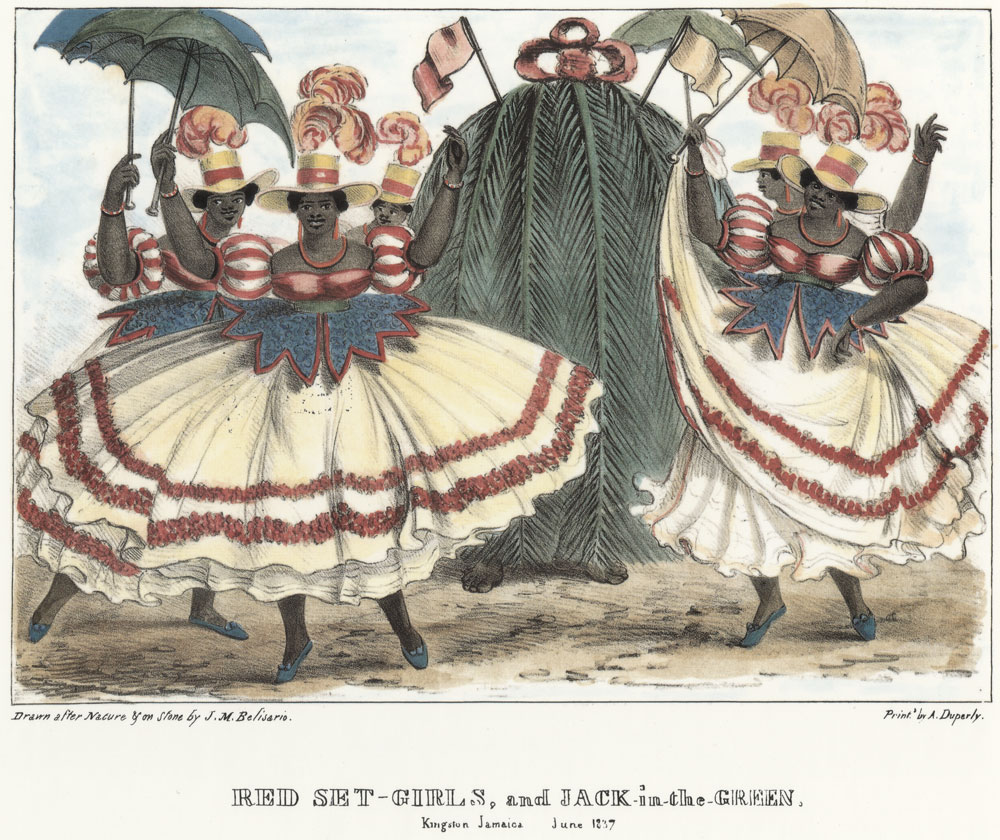

On the streets, Belisario captured the scenes as former slaves and transplanted West Africans poured from their homes to watch singing, merriment and parades of actors dressed in lavish European-style costumes dancing the Jonkonnu, a blended masquerade.

Producing lively and colorful drawings of the celebrations, Belisario -- a white, Jewish, British subject -- would eventually give Europeans their first real views of Jamaican culture.

The Yale Center for British Art aims to bring the same experience to New Englanders through the exhibit "Art & Emancipation in Jamaica: Isaac Mendes Belisario and His Worlds,'' through the end of the year.

"Belisario came to Jamaica at a time when the island was in the middle of a huge change. ... Nobody felt truly at home,'' said Gillian Forrester, the associate curator of prints and drawings and a Belisario aficionado. ``There was always this theme of displacement and assimilation, and a binary relationship between Jamaicans and Europeans in his work.''

Organized to commemorate the 200th anniversary of the abolition of Britain's slave trade, "Art & Emancipation'' is the first exhibition to exclusively focus on the visual culture of slavery and emancipation in 17th- 18th- and 19th-century Jamaica.

The exhibit -- the result of a yearlong global hunt for Belisario and other artists' works, including landscapes by Joseph Bartholomew Kidd, West African costumes and documentary lithographs by Adolphe Duperly -- chronicles the iconography of sugar, slavery and the changing Jamaican topography from the beginning of British rule in 1655 to the turbulent years of emancipation's aftermath in the 1840s.

The abolition of slavery, "was definitely not the end of the story in Jamaica,'' Forrester said. "The period afterward was a brutal one -- it was one of people trying to form an identity.''

"Art & Emancipation'' reflects the struggle, as well as the beauty, that emerges from a country of disparate people. Laid out in eight sections, the exhibit takes visitors through crucial periods in Jamaica's development, beginning with the introduction of slaves in the sugarcane fields, around 1655. Plantation life is depicted in Kidd's watercolor landscapes, and lithographs by Belisario and Duperly document the country's violent uprisings.

Central to "Art & Emancipation,'' however, is the concept of the Jonkonnu dance and Belisario's work surrounding it. Jonkonnu differed from other Caribbean cultural events, such as Carnival, in that it included references to religion, history and moral values, which eventually galvanized a group of African tribes -- the Igbo, Kongo and Yoruba among them -- to create a collective Creole culture.

Belisario was born in Kingston, Jamaica, in 1795 to a Sephardic Jewish family of Spanish or Portuguese origin. He grew up in a cosmopolitan family that moved back and forth across the Atlantic in response to changing economic, religious and political circumstances. Belisario trained as an artist under Robert Hills, a landscape watercolorist and drawing master.

From 1815 to 1818, Belisario exhibited landscape watercolors in London, but put aside his artistic endeavors in the 1820s when he took a job as a stockbroker and shuffled between London and Kingston. Settling in Jamaica in the 1830s, Belisario established a studio, where he produced small-scale watercolor portraits, before embarking upon his artistic renderings of the rebellion.

In 1823, members of Britain's House of Commons and the Anti-Slavery Society in London declared slavery "repugnant to the principles of the British constitution'' and called for its immediate end.

The country experienced several uprisings over the next 10 years until the Reform Act of 1832 effectively abolished slavery in favor of a period of "apprenticeship,'' in which enslaved children under 6 became immediately free, while their elders, although paid, remained tied to their former employers for four years.

The visual images produced at the time reflected a wide range of views toward emancipation. They included images that revealed the horrors of life under apprenticeship -- images used by humanitarian campaigners in London -- to more placid plantation scenes. Originally designed as a series of 12 volumes, Belisario attempted to meticulously record true life in Jamaica through his "Sketches of Character,'' the first of which consisted of four hand-colored lithographs accompanied by text explaining the various customs.